Kim Ng took her seat on the chartered jet. As assistant general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, she was joining the team on a road trip in 2008. Soon the Dodgers players started filing onto the plane, and a flight attendant began taking drink orders from staffers. When she reached Ng—pronounced Ang, rhymes with Hang—the flight attendant leaned in close. “So what did you do to get on this plane?” she asked.

After nearly two decades in baseball front offices, Ng had become accustomed to the condescending glances, outright hostility and attempts at intimidation that come with being the only woman in the room. But this was, well, something else entirely. So Ng decided, as she had so many times in her professional life, to have some fun with the situation.

“Do you really want to know?” Ng said conspiratorially, teasing a salacious secret.

“Yeaaah,” the flight attendant replied, barely containing her enthusiasm.

“See all these guys?” Ng said.

“Yeaaah.”

“They all work for me,” Ng said.

Speaking during a video interview from a hotel room in Miami where she had been staying for the past month or so, Ng laughs recalling this conversation. “She slinked away,” Ng says. “The point was, Why are you asking me this?”

Ng was named the general manager of the Miami Marlins in November, becoming the first female GM in the history of major North American men’s pro team sports and the first East Asian American to lead a Major League Baseball (MLB) team. She had interviewed for GM positions at least 10 times over the years, only to be passed over for someone else. But her hiring by the Marlins was not just a personal victory—it was widely celebrated as a breakthrough with the potential to place more women in traditionally male power roles, in baseball and beyond.

Richard Lapchick, whose Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida publishes an annual report grading the hiring practices of sports leagues—MLB most recently got a C for gender hiring—hails Nov. 13, 2020, the day that Ng’s new position was announced, as the “most note-worthy day for baseball since Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947.” Michelle Obama and Hillary Clinton sent Ng kudos via Twitter; two of Ng’s inspirations when she was growing up, Billie Jean King and Martina Navratilova, also cheered the enormity of the moment on social media. On the night of President Joe Biden’s Inauguration, Ng even participated in the virtual festivities, sharing words from Ronald Reagan’s 1981 Inaugural Address celebrating peaceful presidential transitions. “It is unbelievable yet totally deserving that Kim has ascended to a position of power, influence and leadership,” King tells TIME. “Kim Ng being a GM of a major sports team is a strong indication that if you can see it, you can be it.”

Women have made notable advances across men’s sports during the past year. In September, an NFL game was the first to feature female coaches on both sidelines, Callie Brownson of the Cleveland Browns and Jennifer King of the Washington Football Team, as well as a female official, Sarah Thomas, who would later become the first woman to referee in a Super Bowl. In December, San Antonio Spurs assistant coach Becky Hammon became the first woman to serve as head coach in an NBA game when she took over for her ejected boss, Gregg Popovich. And Ng’s ascension is hardly the only sign of progress in baseball: last summer, Alyssa Nakken of the San Francisco Giants was the first woman to serve as an on-field coach in an MLB game, and in January, the Boston Red Sox hired Bianca Smith as a minor league coach, the first Black woman to coach in pro baseball history.

But the boys’-club stench lingers: in February, the Los Angeles Angels suspended pitching coach Mickey Callaway after the Athletic reported accusations that he made inappropriate advances toward at least five women in sports media; Callaway has denied harassment. The previous month, the New York Mets fired general manager Jared Porter after ESPN revealed that he had sent lewd photos and a barrage of unsolicited texts to a woman working in media. “We need more women in baseball,” Ng says. “I think that’s what it points to.”

As the most visible female executive in men’s sports, Ng can go a long way toward shattering the outdated idea that female leadership won’t translate in that male-dominated world. At her introductory press conference, Ng, fully aware that bad actors can point to one woman’s lack of success as an indictment of all women holding top decision-making spots, said that when she got the job, “there was a 10,000-lb. weight lifted off of this shoulder. And then after about half an hour later, I realized that it had just been transferred to [my other] shoulder.” She acknowledges that the burden isn’t fair. “But it doesn’t matter,” she tells TIME. “That’s just the way it is. In baseball, we talk about working off the ideal. But you don’t always get that. So you just have to keep rolling.”

Ng, 52, grew up playing stickball in Queens, N.Y. One manhole cover served as home plate, a parked car to the right was first base, another manhole cover down the street was second, and a parked car to the left was third. She was always the only girl. “I grew up a tomboy, for sure,” Ng says. “Always the oddity.”

Her father, who died when Kim was 11, had introduced his daughter to baseball. She slept under a poster, sponsored by Burger King, of the 1978 World Series champion New York Yankees. Baseball’s slow pace—the average sports fan’s biggest complaint about the game these days—-actually drew her in. “It gave me time to ask questions,” Ng says. “It gave me time to socialize and to be curious, and not necessarily be completely entranced.”

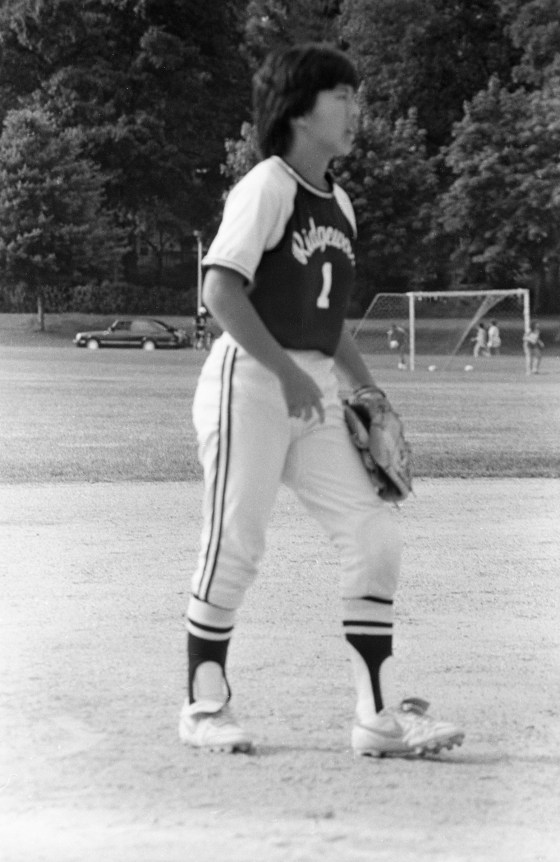

When her family moved to Long Island, she took up organized softball. She was then the star of her team at Ridgewood High School in New Jersey and continued her career at the University of Chicago, where she hit .388 as a junior. She played multiple infield positions and emerged as the unquestioned team leader. “She was one of those loud people on the field,” says Rosalie Resch, an assistant athletic director during Ng’s years on campus. “There was no question how many outs there were.” In one photo from the time, Ng is kneeling at the front of the dugout, eyes honed in on the Chicago hitter, more immersed in the action than anyone else.

Her senior year, Ng served as president of the school’s Women’s Athletic Association, a group of students representing the interests of female athletes, and wrote her public-policy thesis on Title IX, the landmark law mandating equal opportunities for female student-athletes. She decided to pursue a career in sports, maybe in marketing or sports information. But soon after graduation in 1990, Ng interviewed for a baseball-operations internship with the Chicago White Sox. Dan Evans, then the team’s assistant GM, was impressed with her smarts—and the fact that she didn’t get flustered when she entered his office and found a spit cloth on his shoulder and his 3-month-old baby napping in a crib.

He hired her for the unpaid gig, which led to an awkward conversation between Ng and her mother. “Here I am paying $25,000 a year for the University of Chicago,” says Ng’s mother Virginia Cagar, who wanted her daughter to go into banking like she had. “I asked her, ‘Well, what’s your salary?’ And she hemmed and hawed and finally came out and said, ‘Ahhh, nothing. I’m working for free, Mom.’ I said, ‘Return on investment. What happened to it?’”

At one point, Ng had three jobs: she’d finish work with the White Sox, then change in her Toyota Tercel on the way to her assistant coaching gig with her alma mater’s softball team. Then she’d head to a research assistant’s position at the University of Chicago’s Chapin Hall, which focuses on children’s policy. She bought a cushion at Walmart and crashed on the dorm-room floor of her younger sister, who was still a University of Chicago student. “A total housing violation,” Ng says.

But it paid off as she started rising through the White Sox ranks. She’d hold the radar gun, do data entry, alphabetize draft cards. She’d carry legal pads around the office, peppering Evans with questions, taking diligent notes. “She learned everybody’s job because she was willing to help with anything,” says Grace Guerrero Zwit, who has worked nearly 40 years with the Chicago White Sox and is now the team’s senior director of minor-league operations. One time, a male staffer asked Ng to fetch a coffee. No thanks, she said, I don’t need a cup right now. “Some of the older guys and baseball scouts, they were just like, What is this girl doing here?” says Zwit. “They just didn’t get it. She didn’t back down from anyone.”

Ng soon took the lead in arbitration, baseball’s strange ritual that calls for a team to make the case before a panel that one of its players should not get as big a raise as he and his agent think he deserves. She recalls a case she presented in front of Scott Boras, the most powerful agent in baseball, and a White Sox player she asked to remain nameless. She started off nervously, which gave the player an opening to stare her down. “That just got me going,” Ng says. “Your competitive nature takes over and it’s like, ‘O.K., if that’s what’s going to go on here, then I’m going to get there too.’” The White Sox won the case.

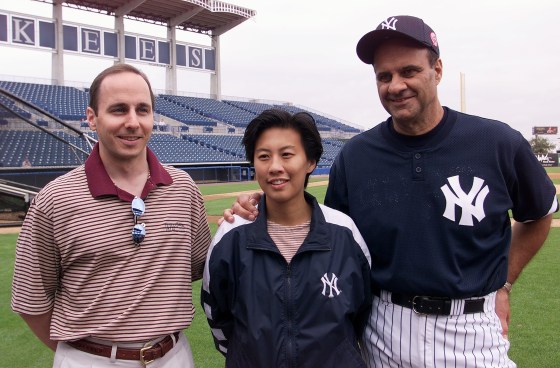

Ng left Chicago in 1996 and joined the American League office as director of waivers and records. Although the job title sounded as if her office should be placed at the back of the library among the stacks, the position helped her connect with executives throughout the league, who relied on her to avoid making technical mistakes in executing trades and other transactions. Brian Cashman, as assistant GM with the Yankees, was impressed with her acumen, so when he was elevated to Yankees GM in 1998, he offered Ng the chance to replace him in his previous role. She would now be working for the notably demanding and volatile Yankees owner George Steinbrenner.

She had another phone conversation with Mom. “Maybe, Kim,” Cagar told her, “George Steinbrenner will let you go to night school for your law degree.”

The Yanks won three straight World Series. Grad school was very much out. “She was one of the knights at the round table during one of the most historic times in Yankees history,” says Cashman. Mom started to warm to the whole baseball career. “It was a very gloating period,” Cagar says. “Especially when she could get me a parking space at Yankee Stadium in the players’ lot.”

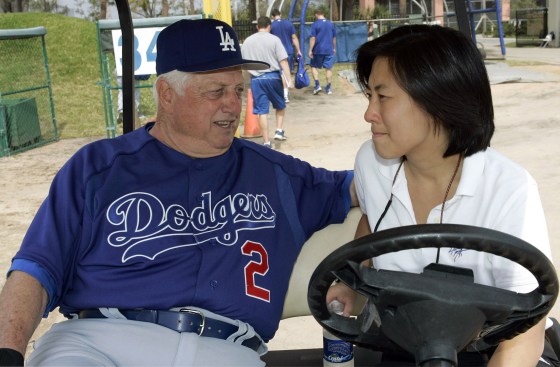

In 2002, Evans—who had become the GM of the Los Angeles Dodgers—hired Ng as his assistant GM, and the idea of getting a top job began to crystallize in her mind. It was always going to be a challenge, but in 2003, she got a taste of just how unwelcoming the sport could be. At the hotel bar one night during the general managers’ meetings in Arizona, former major league pitcher Bill Singer—then a scout for the New York Mets—asked why she was there and mocked her Chinese heritage with a fake accent. He soon was fired. (When contacted by TIME in February, Singer declined to comment.)

“I was just extraordinarily pissed,” Ng says now. At a meeting with Dodgers and Mets officials at the hotel after the incident, Singer started to apologize. “I just said, ‘Stop, stop,’” Ng says. “And then I had to tell him what I thought in front of a dozen people. I just told him to save it. Because the only person that was going to feel better after he spoke was him. I said it was really interesting that he picked the only person in the room who wasn’t going to throw him through a window after what he said.”

Ng has spent her whole career dealing with people’s preconceived notions of her. “People treat you differently,” she says. “There’s always going to be testing.” She recalls going into meetings accompanied by a 6-ft.-3 guy on her staff who was 20 years her junior. “All the conversation will be toward him,” Ng says. “All the eye contact will be at him. And he’s looking around going, ‘Who is this? What’s going on?’” This sort of thing happens again and again. Ask other women, Ng says. “Because I’ve given this example, and they all nod their heads, like, absolutely.”

Ng toiled for three decades before running her own baseball team, despite being an early adopter of baseball analytics. In Chicago, Ng became conversant in the advanced statistics that started enveloping– the game at the turn of the century. These new tools to evaluate players granted a small army of Ivy League quant types—all men—-access to top GM jobs. Ng brings those data skills to her new position, along with an appreciation for the human side of evaluating a player’s potential and an ability to build trusted relationships throughout the game. “You have a lot of people walking this planet who are extremely smart,” says Cashman. “Or they’re extremely relatable and not very smart. She’s a double threat, where she has a demeanor that allows her to connect.”

She left the Dodgers in 2011 to join the Commissioner’s Office, where Ng oversaw international baseball development and scouting activities. One of her tasks was directing baseball activities in the Dominican Republic, where for years local agents—called buscones—have skimmed off exorbitant portions of the signing bonuses awarded to young prospects. These men had little interest in changing the system. But Ng held firm. “I called somebody else who was there, and he said, ‘Oh, she just gave them an ass whipping,’” says Peter Woodfork, MLB’s senior vice president of minor league operations. “Everyone initially was like, she needs security. And afterward, they were like, I think she’s just fine.”

Still, her dream job, architect of one of baseball’s 30 clubs, continued to elude her. Ng was at times offered interviews she didn’t think were sincere. The teams, she strongly suspected, were just checking a box. But she felt a duty to power through the process, if not for herself, then for women following in her path. “It just had to be somebody who kept that notion of a woman running a club alive,” Ng says. “It’s pretty crushing when you get turned down. To put myself through that was not always fun. But I thought it was necessary.”

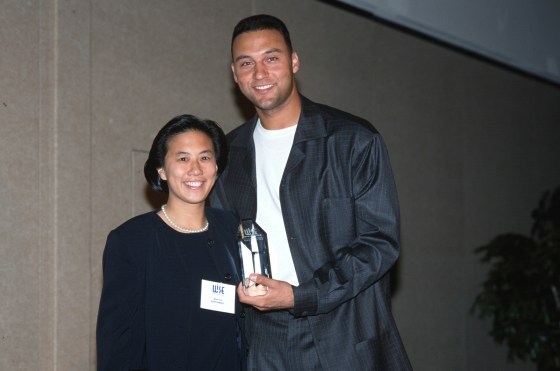

After losing out on jobs with the San Diego Padres in 2014 and San Francisco Giants and New York Mets in 2018, Ng heard last fall from former Yankee great Derek Jeter, CEO and co-owner of the Marlins. He had known her from their Yankees days; he even presented her with an award at an event for women in sports business in 2000. During their final Zoom call, Ng launched into her closing pitch before Jeter stopped her, making clear the job was hers. Ng paused. Jeter wondered why she wasn’t joyous. “In work contexts, that’s one of your tools, that people don’t necessarily know what you’re thinking,” Ng says. “I’ve trained myself to do that. Plus, I was just in disbelief.”

Finally, she smiled. Many others did too. A group chat of women in baseball—about 80 strong—buzzed when the news of Ng’s hiring broke. “It’s important for people like me to have female bosses and role models and mentors,” says Jennifer Wolf, life skills coordinator for the Cleveland Indians. “But it’s also important for girls who are growing up now, and boys growing up now, to see that being a person in a leadership role is not limited to white men.”

Samantha DiGennaro, a PR-firm CEO who played softball with Ng at the University of Chicago, was leading a Zoom meeting when she spotted the news on her cell phone. (She cops to defying her own no-looking-at-phones edict.) “I started welling up a little bit,” she says. “They were tears of joy, tears of pride, tears of nostalgia from my years playing on the field with her. But they were also tears of reckoning. For every woman who has a dream.”

Before her hiring was announced to the public, Ng summoned her four younger sisters to their mother’s senior community in New Jersey. Sitting on lawn chairs near a gazebo, Ng played them a clip on her iPad of Jeter presenting her with the award from all those years ago. “I’m scratching my head, thinking, Why is she doing this?” says Cagar. Then Ng told her family that she and her husband were moving to Miami. “Some faces among her sisters lit up,” Cagar says. “They’re a little faster than I am.” Ng told her mother that Jeter had hired her to be Miami’s GM. Though COVID-19 precluded the kind of group hug you see after the final out of the World Series, they all screamed in unison and jumped in place. Cagar uttered three words.

“Long. Time. Coming.”

The outpouring of support surprised Ng. She says at least 500 people have told her they are now Marlins fans. Sheryl Sandberg reached out on email. So did Ng’s eye doctor from the early 1990s: “He said, ‘This is Dr. So-and-So from Lens-Crafters.’” Cagar visited her dentist a few months ago wearing a Marlins mask. “She looked at me,” Cagar says. “And I kind of gave her the eye signal.” Gloating time, once again. Yes, Cagar told her, Kim Ng is my daughter. “And she was delighted,” says Cagar.

Some see significance beyond gender. “For MLB, China is a potentially huge market,” the South China Morning Post wrote in a November editorial. “With Joe Biden as President-elect, some Chinese hope there will be a reset of bilateral relations. Sport often makes great diplomacy. And who can be more inspiring at the moment than Chinese-American Kim Ng?”

Her task—building the Marlins into a consistent winner—won’t be easy. Ng won’t have the big-market resources that were available to her in New York or Los Angeles: Miami typically ranks in the bottom third of MLB clubs in payroll. South Florida has been a boom-and-bust baseball market, mostly bust: though the Marlins went on out-of-nowhere runs to World Series titles in 1997 and 2003, the team has finished 21 of its 28 seasons—-including every single year in the 2010s—with a losing record. (The team was 31-29 and won a playoff series in the abbreviated 2020 season.)

With the ongoing pandemic, working conditions aren’t ideal. Her first teamwide address, to some 140 Marlins players and staffers throughout the organization, was on Zoom. “Your teammates will rely on you more this year than in any other year,” she told them, “because much of this is about staying safe, and keeping your teammates safe.” During Miami’s first day of full-team spring training in February, Ng moved around the fields, watching batting practice from the first-base dugout, checking out bullpen throwing sessions. “I was really trying not to make them nervous in any way,” says Ng. “Unfortunately, I’m pretty easy to pick out in a crowd of people.”

Ng knows more eyes are now on the Marlins, thanks to her historic role. “I think there are degrees by which I will be judged,” Ng says. “If the Marlins don’t make it to the World Series, I don’t think people are going to see it as a failure.” She pauses. “I’m sure Derek will see it as a failure,” she says with a laugh. “But look, I also have great confidence. I don’t think we’re going to fail. We all want the same thing. And that’s to bring another world championship to Miami.”

On that victory plane, there will be no question what she’s doing there. Everyone will know Kim Ng. —With reporting by Barbara Maddux

from TIME

0 Comments

Give your valuable feedback !